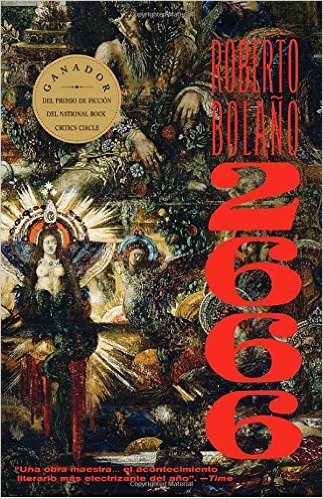

I finally finished Roberto Bolaño’s novel 2666 last month (912 pages in English; 1,136 in Spanish). It represents a year of reading for me (with some other stuff thrown in, but nothing I stayed with or finished). The beauty of books, as opposed to TV and movies, is that you can take your time and just tackle two or three pages a night for fifteen to twenty minutes at a shot. TV and movies make us think we have to eat whole stories quickly. If you can disavow that habit, and feel comfortable with the slow pace of reading, you will probably extend your life by at least eight years, maybe ten. Besides, 2666 is considered one of the most important novels of the early 21st century. It probably can’t be read quickly no matter who you think you are.

We are living a more global version of the central motif of 2666, the obscure and usually distant connection people have to senseless, random, weekly death that our chosen instruments of law and order are completely powerless to do anything about. It seems, in fact, that the more powerless, random, and senseless murder is in our world, the more those chosen instruments become entangled and part of the problem. What is most interesting about 2666, though, is not the mess of chaos and murder that brushes up against so many of the disparate characters and plots as the way people incorporate the insanity of all that inexplicable violence into the stories they tell themselves about life so that they can live decently or obliviously or both.

The book consists of five quite separate novellas connected by numerous motifs, themes, and storylines: The Part About the Critics; The Part About Amalfitano; The Part About Fate; The Part About the Crimes; The Part About Archimboldi. Before he died Bolaño went back and forth about whether these parts should be published separately or in toto. His final conclusion was they should be separate. His family and publishing crew spent a lot of time trying to figure out what made the most sense and settled on lumping them all into one gargantuan book. It’s considered one of the greatest novels ever written. Had it been five separate novellas that wouldn’t be the case. Certainly it is a masterpiece.

2666 centers — maybe connects is a better term — on a somewhat fictionalized Mexican border city called Santa Teresa where hundreds of women of all ages have been brutally murdered during the mid-1990s. Most of the crimes are never solved. The story of this city and its murders is based on the real life City of Juarez that sits on the Mexican side of El Paso, Texas where thousands of people have been murdered over the last several decades. 2666 is filled with numerous red herrings, weird scenes, and mysteries that start up then disappear as you go, like ghosts or half-told myths that come out as whispers and seem like late night traps for the drunk and unholy.

The other connecting force in the story is the great fictitious literary author Benno von Archimboldi who is, as is often the case with Bolaño, the poet-warrior-hero of the story — although he isn’t exactly that as well since he’s as much a mystery and a ghost as he is a character. The whole first part is a somewhat hilarious story of academics (if you find academics hilarious) who worship Archimboldi almost masochistically. They manage to spend the bulk of their professional lives either talking about the secret writer, composing books about him, or literally trekking around the world in search of him.

Fog of life situations are all over the place as the stories and parts about stuff move through time and space, from Mexico to Europe to Russia to America to Mexico to Romania. Had I been sitting on this masterful writer’s left shoulder, I would have asked whether he wanted to consider writing into the future which may be the only dimension he did not have us traverse. But why should he? Is the title referring to the year 2666? Six hundred and fifty years from now? And isn’t it generally true that literature is read in the future anyway?

The power of this singular novel comes from how it opens up one’s sense of reality in a truly global world culture that is both crazed and running amok full speed and in all directions at once. The murders of the women are central to everything. They are blatantly described and documented in the section called “The Part About the Crimes.” One after the other after the other — with the lives of central people in the Santa Teresa criminal justice system thrown into that section and stirred and stirred into a stew of vagueness — acceptance of violence against women, romance, rejection of machismo and a recognition that machismo is the cause of all violence everywhere, questions of sanity (for all of us), dark passions at times, and the innocence of rebellion and discord and morality that must always step in when the chips are really down — all of that swims in the darkness of “The Part About the Crimes.” It is one of the most devastating depictions of hell on earth ever committed to paper. It is brilliant. It is repellant. And it is damning, somehow, of us all.

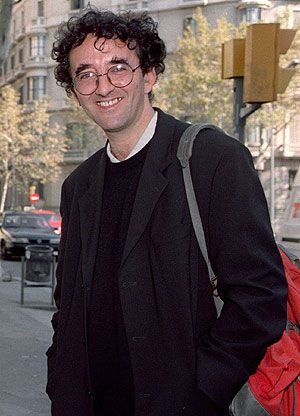

Writing both interesting and new has been achieved here in 2666 by this great, great beloved writer who died far too soon. He has stripped the idea of literary fiction of all it’s bullshit garments and irony. He has swept away every expectation a reader might have. Others have tried this — from Joyce and Proust all the way through to Pynchon, Wallace, and Robert Coover. Most of the attempts you read lead you to a sense of “the writer at play” or “the writer reminding us about how absurd life is.” Bolaño is on a different plane. It really is like he has completely opened up the idea of reality and tuned language to a completely different frequency that is both dead serious and a cosmic dance all at once, with deep meaning and the question of what is real about this global nightmare we are all so happy to tweet about at its core.

For the typical reader, the mysteries (and there are many) that Bolaño offers up require resolution. Of course! You don’t present a quest after a ghostly superhero author without those on the quest finally meeting up with that author. You don’t give the reader an extended story about a guy who breaks into churches and pees and defecates all over them in the dead of night without catching him or at least learning of a motive. And you don’t present 112 extended deadpan descriptions of the murder, rape, and torture of impoverished women and girls (mostly) without the villain or villains being caught and strung up where justice prevails because it absolutely has to. And yet, Bolaño is not so kind. We don’t get solutions or conclusions. Not from the story as told by the author, anyway.

One main reason we read novels, of course, is for all the loose and open realities that scare us to death, realities we are all forced to live daily, to be given meaning, redemption, closure, even transcendence. I should say, perhaps, that is the fundamental idea of fictions in general — whether in book form or on screens or told to us around a campfire. This life we all lead is so powerful and absurd. We have stories and we have the idea of a supreme divine being. That’s pretty much all there is to keep most of us from going insane. 2666 does not deal overtly with that supreme divine being, but it certainly lays bare the idea of story and closure and transcendence as the job of fiction. No. Bolaño has pried open a whole new box of weird in 2666. All that stuff you think that matters about reading fiction? It’s bogus. It’s silly. It’s nothing compared to the maw of darkness and questioning this guy points to.

I don’t recommend 2666 for most people. It’s thick, heady, dense, dark, twisted, maddening, unending, and really makes you feel like you’re caught in a maze. However, I do think that Roberto Bolaño is one of the more worthy authors I have encountered in the last decade (along with Joy Williams, Lucia Berlin, Elena Ferrante, and Haruki Murakami). I would suggest, if you’re interested in Bolaño, that you check out one of his short story collections. I don’t know if other’s see him this way, but I see Roberto as very gentle and tenderhearted about all the things that make life a fucked up mess, but wild and goofy, too, like a coyote clown who has been around the block a few times and learned that love is all there is the hard way. Only he’s not saying that. He would never say that. Because that’s just too weird even for those of us still alive in the 21st century. There’s got to be more than that. There just has to be. Love is private. It’s the only thing you can’t open up. Isn’t it?

Related articles

Also published on Medium.