I’m working on ten separate book projects these days — four novels, two memoirs, two collections of related stories, and two titillatingly weird erotic chronicles about masturbation in the modern world. These last I intend to publish under pseudonyms. 90% of the work I do is on my laptop, a rather trustworthy MacBook now seven (7) years old.

In addition to the ten big projects I’m working on I have over fifty short stories in various stages of undress that always seem to be shivering on the white screen I look at every day. Some of these stories are just notes and scraps of dialog, but the majority are nearly finished drafts or, perhaps, completed first drafts that I am not so happy with.

By the end of 2014 I hope I’ve got a publishing deal or two for a few of the books I am working on. But I bet I’ve added another project or three to my list, as well as a half dozen more stories-in-progress. Who knows how many of these projects I am juggling will ever move to finished product and find their way to market?

I’m going to guess there are a few hundred thousand people out there right now working as crazy independent writers just like me. But what happens when one of us dies? Maybe we’ve published a couple books (or more). Those are relics that families will want to hang onto and pass along to descendants, hopefully. The good stuff, though, the unstirred, raw, honest, hokey, and maybe even important stuff, is sitting on our computers in weird places.

This is a problem that has bothered me for a couple decades now: when I die (I’m 56 and healthy, but I know it’s coming in 20 years or so) I will have published a few books, but my current laptop holds the bulk of my hopes and dreams and improvisation, my honest observations about how fucked up the world is, and maybe even a few important insights on love and beauty and how they’re magic enough to make life meaningful.

I’m sure there are plenty of writers who are mortified by the idea that someone would read their unpublished work — heck, from Kafka to Salinger, there are some awfully talented scribblers who felt it best that no one know their naked half-thoughts and fitful hidden moments with ideas and such. But why the hell did they put all that stuff down on paper (or screen) if they didn’t want anyone to read it?

Are you so proud that you think an unfinished idea should never be seen? Personally, I subscribe to the basic assumption that when I’m dead, I’m dead. My clothes and books (and three guitars) will remain. I trust my family to do with that stuff what they will. My old album and CD collections are shelved and boxed in various places throughout our house. My iTunes collections, Spotify playlists, and YouTube “Likes” are a separate matter, but I don’t own any of that stuff, really, so who gives a shit.

What I wrote, though, that’s what’s left of me. I can’t say I’m proud of everything I’ve committed to blank white spaces in my little corner of the universe, but I don’t mind anyone reading the embarrassing or half-witted jottings of my somewhat simple mind. I feel confident that buried in all my incomplete work are little gems of me and my perceptions of the world that I actually want my children and, for that matter, my great grandchildren to read once my body has turned to dust and my DNA is bonding with maggot babies and worms.

The New Yorker just posted an excellent quick-read on this issue called “The Digital Life of Salman Rushdie.” It’s about Salman Rushdie’s archives, but you’ll get the gist of a lot of the weird problems that digital creativity brings up when you read it.

I write this now partially as a reaction to The New Yorker piece. Rushdie has the hot breath and extra saliva of archivists, historians, and bibliophiles worrying about his work. But those of us meager enough to be riding in the hoi palloi section of the bus ain’t got no one professional to curate about our work. And yet, it’s there. And for some of us, we may not be Salman Rushdie, but what we do every day tucked away in our little rooms is, quite frankly, just as important and meaningful as old Sal’s efforts…important to a few people anyway…hopefully.

There may, in fact, be a new little cottage industry that will form around this problem here in the Age of the Independent Author Who Has Given Up on the Publishing World. Indie Archiving would be an awesome and important job, maybe a sideline for consulting copy-editors or disillusioned associate agents. For, say, $500 they would take the dearly departed’s laptop and pull all the literary work into an archived CD. For another $500, plus the cost of publishing, they would create a bound hardback of all that work. Should editing be requested, standard fees would apply.

Seriously, think about it. You as a committed and serious writer could get hit by a Prius tomorrow (and die). In my mid-40s I had a bout with gastric inexplicability that landed me in the hospital on and off over an entire summer. It took them six weeks to diagnose the problem. The night before my operation, one of my doctors came in and told me that if they hadn’t caught this, I would have died in a couple days.

The reaper comes when the reaper wants to come and there’s nothing you can do about your digital life once that happens. If you’re capable of being a realist on this little matter of death, and you happen to be an author, your worst fear shouldn’t be “I won’t be alive!” (which is sad, for sure), but that your family would just wipe your hard drive and reformat your computer for little Mikey to use.

Worse, if you have a computer that’s seven years old like mine, they may just put it in the pile of “To Be Recycled Electronics,” and let it gather dust for another seven years until someone gets their act together and sends it to the county hazardous waste drop-off.

I will leave you with a few tips, then. I’ve been thinking about this ever since 2004 when I had my summer of gastro-intestinal fun.

1. Save all your work to one master folder. You can be as sloppy as you want inside that folder, but make sure you haven’t got little piles of half finished writer’s poop all over your hard drive.

2. When you upgrade computers, keep master folders from each computer on the new machine. You can burn that to a disk if you want, but make sure you also put that stuff on your new computer, and give the folder a logical name (I have two of these on my laptop with the computer’s name followed by the word “Archives”).

3. If you have passwords for The Cloud, your blogs, WattPad-type on-line writing worlds, etc. make sure you have a hardcopy of those passwords that’s easy for people to find. I have a reporter’s notebook called “Keys” in a little cubby on my desk. I even have passwords for email and website accounts for my pseudonymous erotic authoring selves in there.

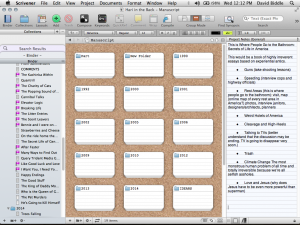

4. Try to use one type of computer system and one of the main word processing applications for your work. I have been using Macs since 1988. I will use Macs until I’m done for. I used MS Word for the first 34 years of my digital writing career. You gotta figure Word is like a cockroach and will be around until after civilization succumbs to global warming. I still use Word for finished copy when it’s time to publish or submit, however, in the past two years I’ve switched all my draft work over to Scriveners, a super-duper author’s word processing tool (highly recommended). As long as I have the software on my computers, my survivors will always be able to read my files.

5. It makes sense to back up to many different technologies, but you need to be careful. If you backup bits and pieces here or there, you are creating an archivist’s worst nightmare. As I’ve suggested, master folders simplify things pretty well. My “Current Projects” folder sits on my computer desktop. I back that up about once a month to Dropbox, two different thumb drives, and the main backup server we have on our network. If my computer could talk to The Cloud, I’d pop everything up there too. Someday the love of my life will let me buy a new computer…

6. This might be weird or painful, but you need to have a talk with those you love about this archived stuff issue. I’ve talked unofficially with my wife about all of this several times over the past decade. My oldest son is 26. I actually plan to sit him and my wife down before the end of this summer to make sure they understand that there’s a shit-load of material on my computer I hope they will want to access for some familial purpose someday even if it’s weird. I say this could be a painful conversation because some authors I know have family members who don’t take what they do seriously. Trying to have a meaningful discussion with loved ones only to have them laugh in your face would really suck. But you gotta do it. That dark, secret avenging Prius is out there waiting for the right moment.

7. Lastly, you may want to literally (ha!) put in your will who you want your archive to go to. Right now, I trust my wife and know that she will handle my leftovers and unfinisheds respectfully. However, some people may have friends or siblings or colleagues who are better choices. To be honest, I plan on living long enough to have at least one grandchild who loves serious fiction as much as me. I plan on steering them away from a career as a novelist (write screenplays, if you must, but there’s no money in novels folks…that’s what they mean when they say “The Novel is Dead”). Still, a young writer can appreciate the archaic fits and starts of an old-school artist who grew up when stories were something to share one reader at a time. It’s a form of guided telepathy after all. Besides, old grandpa had nothing but the best intentions.

Conclusion

I’m sure you can come up with some more pointers I’m leaving out. Please leave them in the comments section here, by all means. You could, for instance, get all worked up about this issue and put your own archive together. I suppose if you were given a year to live, that might be a worthy use of your time, if you really don’t feel like you have anything better to do. But I don’t recommend it. Writers need to spend time reading, writing, and living their lives while they got ’em.

Let me conclude this post with a little aphorism that came to me in the middle of writing this:

“If a book or a story only sits on a writer’s hard drive, it actually could be heard in the forest if someone reads it out loud in the future after the writer is dead and gone.”

Of course, that person needs to be in an actual forest reading for that aphorism to work properly, but you get the drift, I’m sure.

Okay. Get back to work.

One thought on “What Happens When Indie Authors Die? The Problem of Digital Archives and the Avenging Prius”