Near the end of my senior year of high school, I asked my favorite instructor for advice on becoming a writer. Mr. Stawski was an extremely gifted English teacher, a PhD with 30+ years of teaching under his belt, certainly the most respected faculty member at our high school. He’d held a party for our Shakespeare class at his house. I was in a small group of students lingering after because it was so great to be around such a wonderful human being. I also wanted to hear his thoughts on what we should all be thinking about as we graduated and then headed off to college. Asking for advice on writing was also my way of telling him that I might be serious about pursuing a career as an author.

Mr. Stawski’s advice was simple and obvious. He looked me in the eyes and said: “Read as much as you can. People say writers need life experience, and I can’t argue with that, but it’s more important to read anything and everything–especially over the next decade or so as you mature.”

I took that advice to heart. I went to a college where reading (especially original texts) and debate about what we had read was the basic form of pedagogy. I read for pleasure, too. I’m an extremely slow reader, so it’s not like I just read “anything” whenever, but I certainly was ecumenical in my approach to books. There was a long period there where I went back and forth between thrillers and science fiction novels by the likes of Robert A. Heinlein, Robert Ludlum, Isaac Asimov, John le Carré, and Arthur C. Clark. I also went through a six month existential phase, devouring all the fiction and semi-autobiographical stories I could find by Sartre, de Beauvoir, and Camus, along with Beckett’s and Stoppard’s and Ionesco’s plays (there were many others that I can no longer recall). There was also a significant detective mystery period just after graduate school, reading everything I could find about the great detectives Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee (Tony Hillerman), Bony Bonaparte (Arthur Upfield), and Easy Rawlins (Walter Mosely). (It’s funny, I didn’t realize it until years later: all of those stories are about racially ambiguous outsider protagonists, just like me).

Sometime in the mid-’80s I launched off into studying fiction-writing seriously (Please note, and I don’t think Mr. Stawski would have approved, but I took as little as I could of English and writing classes in college. Mostly, I loved anthropology and studying the history of science. But I also didn’t want to learn how to think about books from others).

Once you graduate from college, it generally takes a decade to de-educate yourself, if you are so inclined. I began with works by Graham Greene, V.S. Naipaul, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Alice Munro, Julio Cortazar, Nadine Gordimer, Alice Walker, Milan Kundera, and Jorge Amado. Somewhere in there as well I read a number of books by Henry Miller, Jack Kerouac, and Anaïs Nin. William Styron, Peter Matthiessen, and Robert Stone also took over my mind for a while there. And I was enthralled with poetry by everyone from Galway Kinnell and Gary Snyder to Pablo Neruda, W.D. Snodgrass, and e.e. cummings. Mr. Stawski did not say to read and enjoy, but that’s what I figured out. Even today, more than forty years later, I am currently entranced by works from the likes of Elena Ferrante, Joy Williams, Lucia Berlin, Roberto Bolano, and Haruki Murakami. (Note: I have a hard time, and always have, with Updike, Nabokov, Bellow, and Roth).

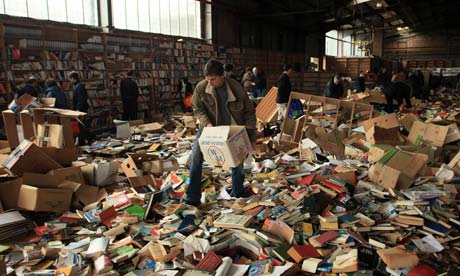

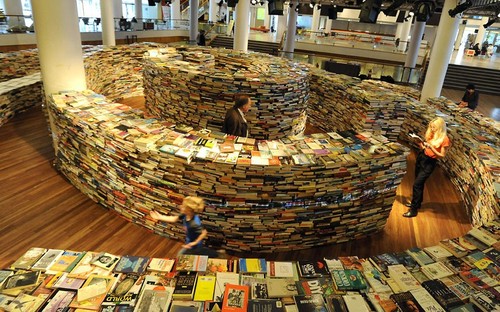

Sorry to name drop. My point is not to create a pile of books and writers to impress or recommend. I really just want to get across that I’ve been doing my best to read “anything and everything” for a very long time.

Still, the question I keep coming back to these days is whether all that reading helped me become a better writer. You have to be careful. It is very easy to fall into echo chambers of your heroes. For a few years there, I read everything I could find by Annie Dillard. I wanted desperately to be able to just come up with one essay that might touch what she touches in the soul of the reader. However, after a while I began to notice that all my draft work kind of sounded like a really dull and dimwitted version of Ms. Dillard (who is one of the best writer’s America has ever produced, I might add). I learned the same lesson over and over through my obsessions with work by other great authors, like Barry Hannah, Joy Williams, and Lucia Berlin. There were others as well. My education has often been a sordid affair of learning, pretending, forgetting, becoming enthusiastic, and re-learning all over again.

That sordidness leads us to my conclusion: I totally got the advice to read the crap out of things, but I never asked why.

I’m sure there are a good half dozen cogent and sensible answers to that question. There have been so many voices bouncing around in my head over the years. Reading certainly does that to you if you let it. Over time you begin to get a sense of all the things you can do with language and stories. Anything is possible in the written world. If you think you want to be a writer, you have to deal with the strange, mysterious infinity that your linguistic imagination realizes is right outside the front door–a dangerous monster, but also a kind, silly giant.

The biggest lesson I’ve learned from all the reading I’ve done over the years is that writers really need to understand what it means to be a reader. That’s not a simple thing. Readers are artists, too, and usually much more sensible than writers.

As much as us scribes want to tell our stories and play with language, the reader is telling themself a story as well when they read what we have written, and it is only partially what we intended. Readers, when they read our work, are also playing with language in as dynamic a way as authors. If you as a writer don’t understand the depth and power of the reader as a partner artist and linguist, your writing is very likely going to miss its mark.

Writing without truly understanding reading and readers is like wanting to go to bed with that attractive weather person you watch every night before you go to sleep: If your fantasy is to have sex with them, then that’s what you will have. But what will they have? You’ll never know. Sex is a one way proposition for people seeking a few minutes of escape.

However, if you manage to fantasize about making love to that wonderful weather person, well, that’s quite different, isn’t it!

Doesn’t matter what type of loving we’re talking about and what the genders are here, when you make love you are there first and foremost for the pleasure of this wonderful person you have dreamed of for so long, naked and smelling so human and desirable — salty, warm, murmuring, nervous, hungry, moist, breathless and ready for joy. (If you don’t have these fantasies about at least one of your local personalities, you need to do some channel surfing until it all comes to you).

Making love is about letting go and fully giving to another person. The same is even more true between readers and writers. It takes years of stories and the scent of books to figure this out. I honestly don’t know if Mr. Stawski had thought things through as far as I have. He was an English teacher, though, which usually means there was a time when he wanted to be a novelist or playwright or short story writer. He may have at least had a glimmer or a tidbit of knowledge about how weird the whole game can be. I’m sure he understood the process of passionate reading and the need for passionate writing. I’m sure as well that he understood the intimacy the reader feels while reading, the somewhat jumbled back and forth between having a conversation with characters (they can be so real and heartbreaking!), the writer (narrator?), and, most profound of all, The Self.

It took a while, but I slowly realized the sorcery of it all by re-reading in my adult dotage books like Invisible Man, The Catcher in the Rye, To Kill a Mockingbird, and The House on Mango Street. These days I am slowly reading the Neapolitan Quartet by Elena Ferrante. The same thing is happening as with all astounding books: a powerful slumgullion porridge mixing the mysterious phantom writer, Elena Ferrante, with two of the greatest characters of any era — Lila Cerullo and Linù Greco — all coalescing, along with the whole of Naples, in the head of each reader, one by one. There is no doubt that a sublime conversation continues to pop up for everyone under the spell of these books as we watch our great invented heroines grow and develop in the world that we all come from.

Thus, no matter how pervasive and ubiquitous social media is these days, it is my deep belief that books are still revolutionary and life changing. Not because they teach anything specific or political one way or another, but because they remind us that we are each truly individuals, and that we have a powerful personal relationship with language, and the stories we choose to understand and tell ourselves and each other carry more truth than anything on YouTube, Facebook, or Twitter. And all the talking heads on cable news, regardless of your politics (or their’s), can appear to be missing the point about most stuff going on around us. That might be disappointing to some. It could be a reason to live each day as a skeptic and a cynic for others. But if you’re reading stories and you’re carrying on that big jumble of a conversation with books and authors and characters and your Self, it’s pretty likely you are someone living in a more significant and meaningful world.

So, thanks Mr. Stawski. I’m pretty sure you never gave our conversation a second thought. You are gone from this earth now. But let me state for the record: Those few sentences you spoke to me changed my life. I earned my way in this world not as a novelist or short story writer, but as an environmental planner, freelance writer, and educator. But I never stopped reading anything and everything, and I never stopped writing fiction and essays when I found the time.

Hey David Biddle. What a great delight to read this. Ahhh…Invisible Man and so many others.