Never tell a character in your head to get lost

A slightly different form of this essay was published in Medium.com

One morning nearly ten years ago, a voice showed up in my head as I was walking up the stairs to my 3rd floor writing room. They were offering the beginning line of a story. By the time I sat in front of my laptop, the voice made it clear that I needed to get to work immediately. “She” absolutely was not going to leave me alone.

No one told us we were going to have a summer-long visitor until the night before that visitor arrived.

Ivy Scattergood

A few months before that, I’d gone back and read a bunch of young adult coming-of-age stories. This was around the time I was becoming acutely aware of the fact that our youngest son was about to leave home for college. I suppose that because I’m a writer going back to my reading roots made sense. Maybe others return to old music, long walks, or pre-parent hobbies.

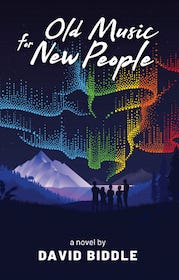

Her name came out of the blue — Ivy Scattergood– as did her cousin’s — Rita Gomez. In just a few hours, the two of them became as real as any two people I’ve ever known in my life. The central dilemmas of their story were clear: What does it mean to be a girl (or a boy, for that matter)? What pushes us so hard when we’re teens to deal so heavy-handedly with our identities? What is “an individual?” And what role do families play in requiring each other to behave in certain ways? Those are the questions and notions that led to the long and funky process of writing my novel Old Music for New People.

The sound of honesty

In 9th grade we were told to choose between two books — To Kill a Mockingbird or Invisible Man. I chose Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, which is still one of my favorite novels. Roughly forty years later, I finally sat down and read To Kill a Mockingbird. It’s amazing that a novel published in 1960 about life in the South during the Great Depression can still be captivating and absorbing. There are certainly a number of problems with the plot, and it’s frustrating to behold small town racism and injustice the way that book does, but the depiction of Mockingbird’s young heroes is about as good as it gets. Scout (Jean Louise), her brother Jem, and their friend Dill are as perfectly rendered as any three buddies in stories anywhere — especially Scout.

If there’s one real deprivation the reader must endure, it’s wishing that we could hear Scout narrate the story in her own more immediate younger voice, rather than as a somewhat distant narrator looking way back on her life. There’s nothing wrong with an adult Jean Louise telling us this story, but the immediacy and quicksilver emotion of that time in her life (and our nation’s) is missing. Shouldn’t novels be about voice first?

Within days of finishing Mockingbird, I re-read J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye where we get a full dose of young post-World War II Holden Caulfield whose voice is defining of non-conformist, individualist teens everywhere. In addition, he has just the right touch of poetics in his tone:

“It was that kind of a crazy afternoon, terrifically cold, and no sun out or anything, and you felt like you were disappearing every time you crossed a road.”

— Holden Caulfield

In reading those two great American novels, I could see quite well the importance of YA fiction for all of us here in the 2000s. If a main goal of fiction is to depict complex emotional truth, there isn’t even a contest, in my opinion, between those two coming-of-age novels (along with Huck Finn) and the most important serious adult-oriented fiction out there…maybe there are a few exceptions.

I also read all the Hunger Games novels and fell in love with Katniss Everdeen. Then I read John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars. After that, I took on Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower. There is something vital and essential about the voice and ethos of coming-of-age narration. Heck, either we’ve all been there, are there as we read, or we’re heading in that direction soon enough.

You write like a girl

At first I worried about trying to “get away with” writing Old Music for New People in the voice of a 15-year-old girl. A good amount of gender ownership has been popping up in the media and literary world these days. Our new networked global culture also seems to be suffering from oddly extreme reflexive intolerance, and a paucity of desire to understand different points of view.

However, worrying about whether you have a right to tell a story in any character’s voice is the kiss of death for a writer. When a character shows up ready to get to work, the last thing you do is tell them to get lost. A writer’s imagination is only ever half full as they do their work. The reader is responsible for the other half.

New People was written in part as an antidote to the dark, dystopian, somewhat depressing stories we encounter in the teen fiction world of today. Modern Dionysian teenage shenanigans are limited. There’s no real bad boy messing up center stage, or truly angsty dudes, or even a cynical douche-bag near center stage. Also, you can forget the stereotype romances that seem to have such appeal these days (although there is romance, just nerdy and vulnerable and good-hearted).

As much as the three Scattergood siblings are front and center in this story (along with their cousin Rita and super awesome stud Bailey Cooper), the four adults in the novel also have huge roles to play, and maybe learn as much as their offspring in the end. Indeed, my generation did an immense amount for modern culture’s ability to handle sexual and gender related identity definitions openly, but somewhere along the line a lot of people forgot it’s a good thing to be fluid and creative in working out who we are–especially in the early stages of adulthood.

I’m pleased, then, with my 363-page novel published in December by The Story Plant. And I’m not worried about the fact that it’s written in Ivy Scattergood’s voice. That’s clearly the way she wanted it. Ivy’s not a perfect person by any means (kind of obvious if you read the book), but she’s as honest and full of life as a teen can be, and has just enough distance from her summer of 2013 to understand how important that honesty is for any reader. And that voice? Ah, trust me, we all have a little bit of Ivy in us.

More on the novel, Old Music for New People, can be found here at The Story Plant website.

Read some further thoughts on young adult fiction in a column I wrote for Talking Writing magazine a few years back called, “The YA Conspiracy — and How I Grew Up.”

Related articles

- How Women Conquered the World of Fiction

- Maurice Carlos Ruffin: On Understanding Voice in Fiction

- Setting the Tone: How to Handle Voice in Your Fiction

- Not the Marriage Plot: On Men Reading Novels in the 21st Century

- Ralph Ellison and the Floating Self

- Watching Fiction Become What It Wants: Stories Crying to Become a Novel

[…] Power of Alt-Lit Poet Steve Roggenbuck DOJ shuts down China-focused anti-espionage program Writing in a Girl’s Voice Never tell a character in your head to get lost You May Not Be Interested in War, But War Is Interested in You the marriage of heaven and hell […]